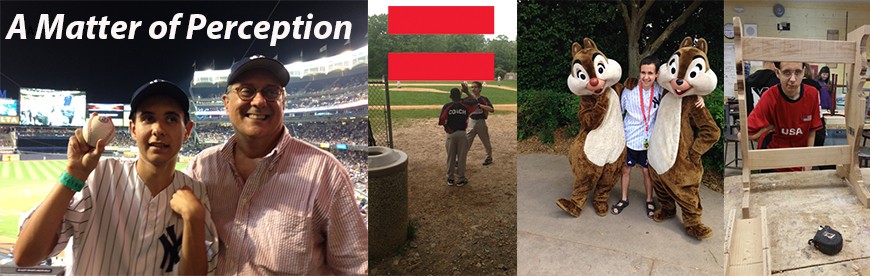

A parent’s perspective on inclusion of children with disabilities

By Bryan Lonegan, Parent, New Jersey

I have discovered the key to inclusion of people with autism in school and the community. You see, it is all a matter of perception. Instead of trying to explain my son through the confines of autism, I have discovered a much more enlightening explanation. I now tell people that he’s French. After all, the signs are there: He speaks an incomprehensible language; has a unique style of personal grooming, demonstrates a disdain verging on revulsion of American cuisine, and is maddeningly aloof.

Now, there are tremendous advantages to being seen as French as opposed to autistic* . If society perceives my son as having autism, a whole host of consequences emerges that, once let loose, cannot be controlled – a kind of Pandora’s Box of social isolation. But if society perceives my son as French, he is just a stranger in a strange land worthy of the time and effort to make him feel welcome among us.

Sure they mean well, but when people encounter autistics they are apt to recall all the reports they have heard about the condition: They – autistics – are captives of their own world and withdraw from the rest of us because our real world has overloaded their sensory systems. Thus, unsure of what to do, otherwise well-meaning people retreat from those with autism, lest they cause the autistics more damage and distress by trying to insert themselves into the autistics’ world. At least that is the generous way of looking at it.

On the other hand, when people encounter a Frenchman, they strive to overcome language barriers and excuse our guest’s unusual behaviors as mere cross-cultural misunderstandings. Indeed, these cultural differences are rendered all the more appealing for their differentness.

So, my son is now French.

As an autistic, he had a communication deficit. As a Frenchman, he speaks a romance language. As an autistic, he was nerdy. As a Frenchman, he is avant-garde. As an autistic, he had an eating disorder. As a Frenchman, he has a point. As an autistic, he had a social impairment. As a Frenchman, he has a . . . well . . . social impairment. But you get the point.

Maybe, now that he is French, his classmates will realize that my son is kind of fun, and invite him to hang out. Maybe, now that he is French, employers will judge him by what he can do and not how he talks. Maybe, now that he is French, people will greet my son on the street and say “bonjour, mon ami!”

* I have purposefully and voluntarily chosen to employ the word “autistic” in this piece, as opposed to the person first narrative. The reasons being, first, that the very point of the piece is a discussion of how the outside world perceives my son and the consequences that flow from that perception. Second, I’m a disagreeable SOB.