“With Friends Like These” - How Not to Write an Amicus Brief: More Lessons On Class Action Law From Mr. T v. Social Media

Jocelyn D. Larkin, Executive Director, The Impact Fund

Prompted by former President Trump’s spate of class actions against Facebook, Twitter, and Google, we recently shared some best practice tips on filing class actions, a topic close to our hearts. A new court filing and order in Mr. Trump’s case against Twitter offers us yet another opportunity to weigh in on a different and important subject to the Impact Fund’s mission—writing effective amicus briefs.

Amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” briefs allow individuals or organizations that are not parties to the case to provide relevant information or argument to the court on issues in the litigation. Amicus briefs are particularly useful when they provide specialized expertise or a perspective distinct from that presented by the parties. To avoid being inundated by would-be “friends,” courts have specific rules that amicus briefs must meet. Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 29 sets out the requirements for amicus briefs in federal appeals courts and is the benchmark for other courts. Aspiring amici (plural of amicus) must file a “motion for leave” to explain why their brief will assist the court and not simply reiterate the arguments of the parties. Duplicative amicus briefs not only tax an overly swamped court and annoy the judge; they may also be seen as circumventing the hard-and-fast word limits that are intended to curb extraneous arguments in the party briefs. The proposed amicus brief needs to be submitted with the motion so the court can know in advance whether the brief does what the amici promise.

Mr. Trump brought class actions against three tech giants alleging violation of his First Amendment rights.

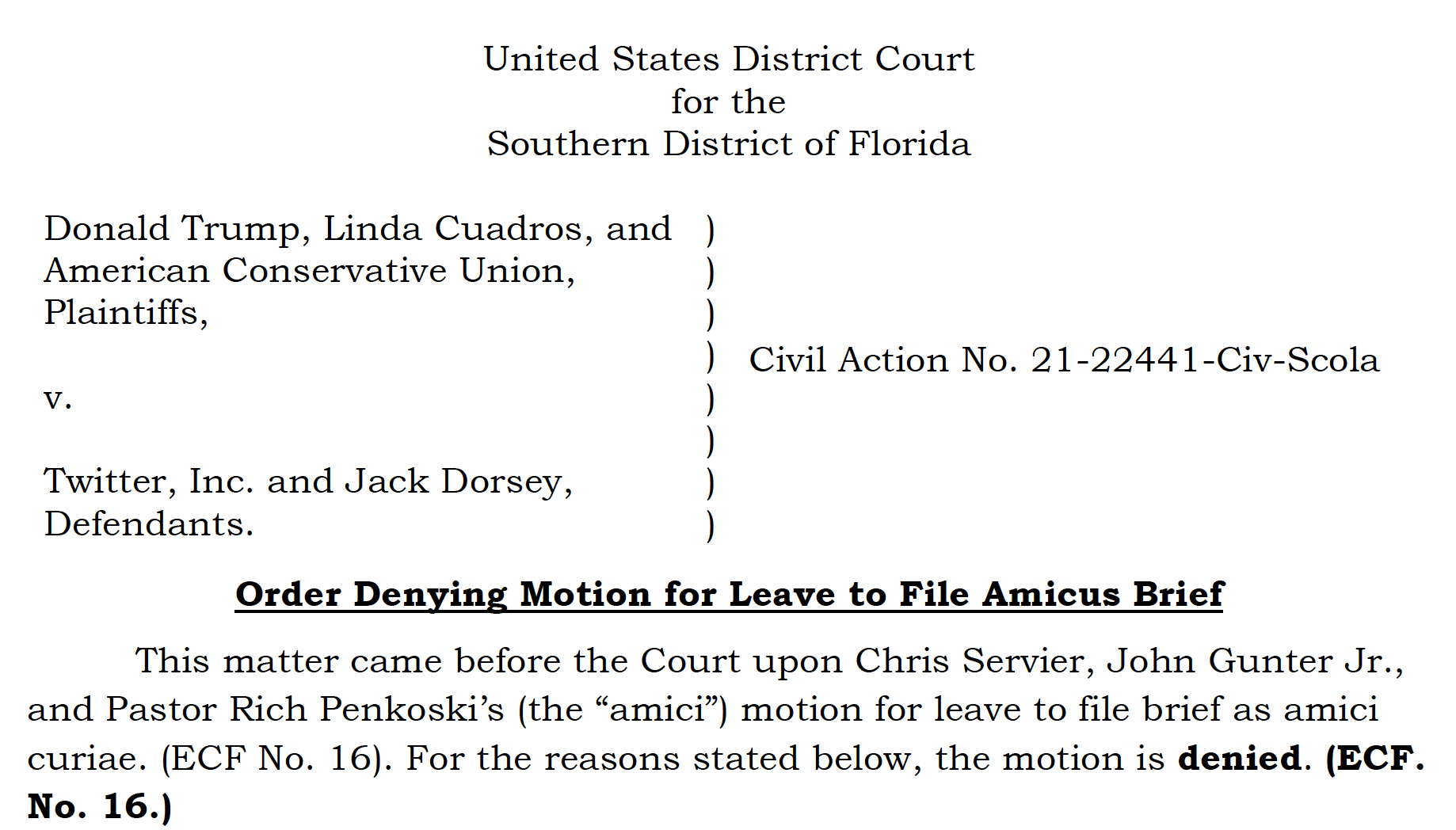

And now, for today’s lesson. Recall that, in early July, Mr. Trump brought class actions against three tech giants for violating his First Amendment rights by banning him from their social media platforms. While the First Amendment only applies to censorship by government actors, Mr. Trump’s lawyers argue that the private companies have become instruments of the government by virtue of the immunity granted to them by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, 42 U.S.C. § 230, a law that protects tech companies from lawsuits over their content moderation. While still in the very early days of the case, the Twitter case docket was abuzz with a motion for leave to file an amicus brief. There’s lots to talk about but—spoiler alert—U.S. District Court Judge Robert N. Scola, Jr. swiftly denied the motion from the court’s wannabe friends.

Who Filed this Motion to Participate as Amici?

In their motion for leave, amici must tell the court who they are and what their interest is in the litigation. Here the proposed amicus brief was filed by three groups: De Facto Attorneys General, Special Forces of Liberty, and Warriors for Christ. I wasn’t familiar with these groups but, fortunately, they provided a lengthy explanation of their mission (albeit in a footnote). “The Amici routinely file comprehensive lawsuits across the United States on different controversial and complex issues that typically concern the ‘culture wars’ and First Amendment issues that are too ‘politically hot’ for the government-funded Attorneys General to pursue.” That statement is reasonably clear but then they add this rather perplexing boast: “In bringing such lawsuits, the Amici – without apology – often end up converting Article III Courts into their own private legislative research commission.” Hmmm. Some of you who are not lawyers may be assuming that this sentence explains some legal process beyond the understanding of laypeople. Not so. It is a mystery or, at best, an unconstitutional violation of the separation of powers. Apparently Judge Scola wasn’t eager to accept this, er, assignment.

Which Party was the Amici Proposing to Support?

U.S. District Court Judge Robert N. Scola, Jr. swiftly denied the motion from the court’s wannabe friends.

Potential amici must identify which party’s position they are supporting, or they can choose to remain neutral, supporting neither side but still providing relevant factual information or legal argument. Here, the amici explain that they are “in partial support and in partial opposition” to Mr. Trump and the other plaintiffs. While they agree with the plaintiffs’ goals of ending “social media tyranny,” they are concerned about the merits of Mr. Trump’s legal positions.

Rather than just carping, here the amici offer an extensive blueprint for Mr. Trump’s continuing legal fight. More on that in a moment.

On What Legal Issue Do the Amici Propose to Weigh In?

Under Rule 29(a)(3), amici must inform the court of the relevance and desirability of their brief. Amici here propose a brief on “the narrow issue of standing.” Our ears perked up at this enticement because, as readers of this blog, you will know that standing is a very important issue. And, because it is a threshold issue in a federal lawsuit, this laser focus would explain why the amici submitted this brief at such a very early point in the case.

Alas, our hopes were dashed. As Judge Scola observed, “although the motion represents that the amici will aid the Court in determining whether the Plaintiffs have standing to bring this action, the proposed amicus brief is silent as to that point.” That’s weird.

Maybe they want to weigh in on the constitutionality of Section 230, the core issue in the case. No, not that either. They do purport to explain Section 230 “so that a fifth-grader can understand it” and describe it as “generally good law.” Who do they think needs Section 230 explained at a fifth-grade level? Amicus briefs are meant to aid the court, not talk down to it. Poor form.

So What is the Proposed Amicus Brief About?

We hear again from Judge Scola: “The brief is exclusively dedicated to advocating for the passage of the Stop Social Media Censorship Act, a proposed bill in Florida.” To be clear, they are talking about a piece of proposed state legislation that hasn’t been enacted and isn’t at issue in this case involving federal law. Is that relevant?

Amici are very proud of their efforts to get “Stop SMCA” passed and include a six-page long footnote—the legal writing equivalent of a party foul—with Dropbox links to versions of the bill in all 50 states. They characterize the bill as “the answer that everyone is looking for whether they realize it or not.” They contend that “the Court must rule that Florida needs to pass a better law, like . . . the Stop Social Media Censorship Act.” I guess this legal team skipped Constitutional Law, Remedies, and the Schoolhouse Rock video.

Relevance aside, amici nonetheless assure the court (in yet another footnote) that their motives are pure: Passage of the Act “will not necessarily help the Amici when it comes to credit and glory, but it will help the Nation, and helping the Nation flourish is the paramount mission of the Amici.” Am I the only one getting chills?

So What is Their Advice for the Trump Legal Team?

Mr. Trump may not be very happy with these would-be friends of the court, who call the causes of action in his complaint “seemingly weak” and “asking too much from the judicial branch.” (If only Mr. Trump were still on Twitter, he could tweet a schoolyard insult at them. Where’s the justice?)

But wait. The amici have included in their proposed brief a detailed plan, tailor-made to please the former President. “President Trump likes to win. So do the Amici. If plaintiffs want to prevail in this legal fight, not just making a political statement, they should take the following steps”:

Seek a stay of the class action litigation that he has just filed.

Have Mr. Trump use his “personal connections to press Governor DeSantis to immediately hold a special session [of the Florida legislature] . . . to pass” Stop SMCA. (I did not make that up!)

Once the Stop SMCA is enacted, reopen the class action and amend the complaint to add a new Stop SMCA cause of action.

The amici have three other suggested causes of action to be added as well. I’m guessing they thought Judge Scola would be happy to wait while they get a new law passed on which to base the lawsuit.

So what have we learned? Write an amicus brief that actually says what you say it says. Write an amicus brief that is about an issue actually in the case. Don’t include six-page footnotes. Don’t suggest that the judge needs something explained at a fifth-grade level. Don’t tell the judge to issue an edict that the legislature pass a better law than the one on the books.

I promise you that, if you follow these directions, you will get all of the “credit and glory” and “the Nation will flourish.”